A Sociological Study of the Livelihoods of the Baigas in the Baiga-Chak Belt of Dindori, India — Conclusions

The text and photographs on this page are copyright by Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. Manish Gangwar is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology at Barkatulla University, Bhopal, India. Pradeep Bose is the Director of the Aaspur Rural Development Project, District of Dungarpur, PKP, Raj., India.

About 90 to 100 years ago, there were, on average, eight livelihoods available to an average Baiga but the livelihood choices now available to their great grandchildren have shrunk and they have no choice but to adopt all livelihoods simultaneously to make ends meet. This narrowing of the bandwidth of Baiga livelihoods has a strong element of coercion, which they would not normally adjust to, in case there were some more relevant livelihoods available to them. The last 25 years have taken away two livelihoods from the Baigas. These are bamboo weaving and fishing. It has almost been ten years since they had to abandon their most-cherished livelihood of basket-making. It was owing to the severe paucity of bamboos in their vicinity and the only other close source of bamboos being owned by the forest department. This did not assuage the Baiga's need for finding an alternative to basket-weaving.

Second the Budhner River that girdles the BCB and offered fish to each Baiga native still runs a 15 Km. long perennial flow, but its previous surfeit of water and fish is now too little to feed the swollen population of 12,000 BCB residents, about three quarters of whom are Baigas.

Of the 8,500 or so Baigas living in about 1,900 households of the BCB that used to always bank upon the forest produce each year to supplement their food and cash needs have also got diminished in size and scope. It is now able to provide produce to only fourteen villages of the BCB. The changing nature of the forest from being multi-species to dual-species has dried many herbs and tuberous and fleshy stem based plants. Baigas also lament the fact that the great wine tree or 'sulfi' (Caryota urens) has disappeared totally from their forests and they have to now ferment inferior sources of liquor like 'mahua' (Madhuca indica) flowers and rice gruels like the hapless Kols and then deign to bootleg it for earning their livelihood. Even after the shrunken forest produce base and only 77 households getting to collect enough forest produce, Baiga-Chak's forest based resources are quite rich and they contribute about Rs. 197,000 where the average annual income per household is Rs. 2,558.44 or (US $47.4 at Rs. 54 per US $). This forest produce is collected by the Baigas and sold in their local markets of Pandri Pani, Dhurkuta, Gopalpur, Kanhari, Jhiria Behera and Chada. Besides, once a week retail roving buyers of forest produce visit the homes of the Baigas in Baiga-Chak and buy the forest produce from the people's courtyards.

The role of Baigas as priests to other castes, like the Gonds, has also been curtailed. There were just four reputed ethnic Baiga healers in 2011, whereas in the old days there would be at least one famous Baiga healer in each Baiga-Chak village. In the meantime, the number of effective and famous Baiga gunias or herb-based healing experts has also dwindled considerably.

The study revealed that the average annual income of a Baiga was Rs. 9,662, which converted to US $ (at Rs. 54 per US $) would be US $179. In other words a Baiga household's per diem income for its 4.59 family members was calculated at below US $0.5 per day. The richest Baiga household would have annual income of Rs.17.447 (or US $323), which is as low as per capita per diem income of US $0.19 per capita.

| Annual Household Income Range (Rupees) | Number of Households in the Range | Average Household Income (Rupees) | Aggregate Household Income (Rupees) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Above 12,000 | 39 | 17,447 | 680,433 |

| 10,001 to 12,000 | 63 | 11,204 | 706,852 |

| 8,001 to 10,000 | 78 | 9,127 | 711,906 |

| 6,001 to 8,000 | 82 | 7,411 | 607,702 |

| 4,001 to 5,500 | 25 | 5,382 | 134,550 |

| 2,500 to 4,000 | 13 | 4,472 | 58,136 |

| Below 2,500 | 300 | 9,662 | 2,898,000 |

Table 13. Annual Income of Baiga Households for 2010/2011.

As Table 13 shows, 38 households, hailing from the lowest two percentiles (or about 13 percent of the Baigas from the BCB) are extremely poor and a further 82 Baiga households or about 27 percent of them are poor. In other words 40 percent of the BCB Baigas are poor. About 70 percent of the poor are from the core area and only 30 percent of the poor belong to the Baiga outposts.

Despite the forty-five-year long presence of the highly advertised central assistance agency for enhancing the development of the so-called most primitive Baiga tribe, the Baiga Development Authority, not a single Baiga household has electricity; just one household has a proper toilet facility and only 37 percent of households have access to clean drinking water from the UNICEF-approved hand pumps. The 63 percent of households that lack access to potable water are perpetually made susceptible to water-borne diseases.

None of the sample households possessed a proper house made of fired-clay bricks with a proper roof. All the houses were made of mud walls and the roofs were of self-fired mud lumps.

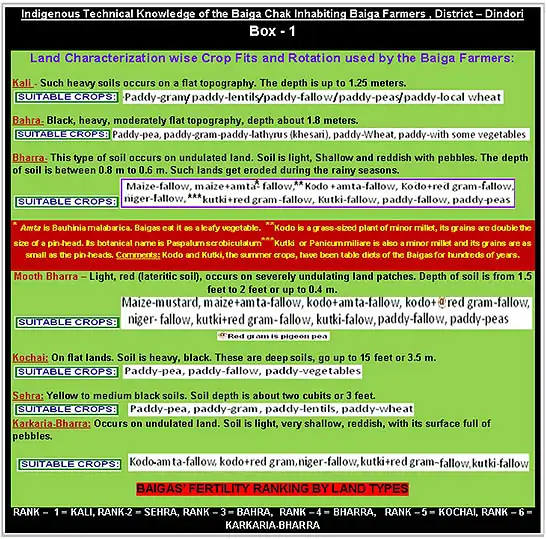

As mentioned in previous sections, it is the third generation of cultivators from the settled Baiga families that have now been engaged in agriculture. It was about 50-55 years ago that the Baigas started settled farming consistently. Based on their two-and-a-half generations' experience of undertaking sedentary agriculture, the Baigas of Baiga-Chak have been able to pool their learning that they obtained while practicing settled agriculture. This is summarized in Box 1 below.

Baigas have been traditional eaters of kodo, kutki and forest based roots. However they picked up the habit of eating wheat chapattis, rice and maize in the last thirty years and have got used to these additional cereals as well. Pej, which in actuality is easy to cook and instant food that entails mixing of ground maize/kodo/kutki with warm water, has emerged as the food of choice for the modern generation of Baigas.

Owing to the shrinking forests and dwindling game, the animal protein content of most of the households has been affected adversely. Domesticated animals like chicken, goats and pigs, however, complement some of the animal protein requirement of the Baigas (see Table 14 below), yet it is not enough to compensate the loss of meat and fish from the open range that they were able to capture earlier. Moreover, because Baiga communities do not know how to efficiently produce cow and buffalo milk, the milk component of their diet has always been very negligible. There may be a genuine case for promoting goats and chicken with the Baigas of Baiga-Chak [10].

| Type of Livestock Reared by Baiga Chak Households | Goats | Pigs | Chickens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Owned | 102 | 90 | 238 |

Table 14. Livestock Reared by the Baigas.

The following three exhibits are based on focus group discussions that we held with two Baiga native groups from Paundi and Kindra Bahera villages. In addition we are very grateful to Mishra and Gupta from the Indian Institute of Forestry Management, Bhopal and Srivastava from MLB College, Bhopal for some of the information presented in these exhibits.

| Rank | Indicator | Event Predicted* |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Excessive flowering of bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris and Dendrocalamus calostachyus). | Drought. |

| 2 | Vigorous fruiting of sal tree (Shorea robusta). | Drought. |

| 3 | Four small mud pieces are placed below a water-filled terracotta pitcher, each facing north, south, east or west. After a couple of hours one mud piece dissolves. | Heavy rains from the direction of the mud piece that dissolved. |

| 4 | Heavy winter frost. | Heavy rains in the next rainy season. |

| 5 | The full moon in Baisakh (approximately April) becomes fully hidden by cloud. | Heavy rains in the current year. |

| 6 | Heavy early winter frost (e.g., around Diwali season). | Good rains next season. |

| 7 | A queening cat finishes delivering her litter in the rainy season. | The rainy season will continue another month for each kitten in the litter. |

| 8 | All black plums (Indian black berries, Syzygium cumini) or bhui amla herbs (Phyllanthus niruri) ripen before the end of June. | A very good rainfall season in the same year. |

| 9 | New leaves appear on Bodhi (Ficus religiosa) and saja (Terminalia tomentosa) trees in late October or early November. | Good rains next season. |

| 10 | Vigorous fruiting of Chironji (Buchanania lanjan). | Heavy rains in the current year. |

Exhibit 1. Empirical Baiga Observation used to Predict Rains. *Baigas observe all the aforesaid indicators and based on a combination of these factors, they predict rains.

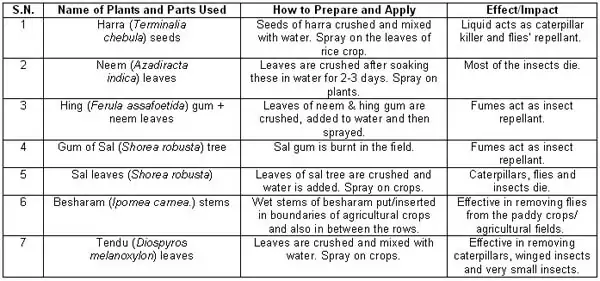

Exhibit 2. Baiga Pesticidal Herbs.

| Plants to be sown in Drought | Plants to be sown in Flood-like conditions |

|---|---|

| Kurthi (Horse Gram, Macrotyloma uniflorum) | Kumhada (Benincasa hispida) |

| Arhar (Pigeon Pea, Cajanus cajan) | Kutki (Little Millet, Panicum sumatrense) |

| Chowla/Jhunjhuroo (Cow Peas, Vigna unguiculata) | Dengra (Graces Warbler, Dendrocia graciae) |

| Urad Black(Black Gram, Vigna munga solanum) | Rawans (Adzuki Bean, Vigna angularis) |

| Bhejra (Solanum) spp. | Sikia (Millet, Persea americana) |

| Kheera (Cucumber, Cucumis sativus) | Salar (Salai, Boswellia serrata) |

| Sanwa (Panicum crasgaliver frumentacum) | Bhalukand (Karikand, Dioscorea pentaphylla) |

| Kang (Kangni, Setaria italica) | Kochai (Colocasia esculenta), Amta (Tinospora cordifolia), Dodka (Luffa Aegyptica) |

Exhibit 3. Diaster Relief Plants.

All the respondents were given a separate, one-page questionnaire asking them about their self-identity, their wish list for development and their taboo-free dream if it were possible to live another life. Table 15 shows the data of twelve respondents. Quantitative evaluations of these responses were not meticulously worked out, as this exercise was conducted particularly to ascertain whether the Baigas were reconciled to their extant self-esteem and possessed ample life-force to live happily their own lives, despite their poverty. And it was apparent from the response-sets generated that about two thirds of them were indeed so and rarely dreamed beyond themselves. It was very unusual to find that there had been about one third of the respondents who, though they did not exactly rue their lot, wished they were richer and had access to more resources and had higher income. Nearly one fourth of the respondents hoped against hope that somehow along with the riches they got multiple wives. (In fact there were only two male Baigas in the entire BCB who had two wives.) Some women found it hilarious to be reborn as rich polygamous men. Meanwhile, it was curious to find that very few younger Baigas (aged below 40) dared dreaming of unusual and off-beat things. And it happened to be some of the older persons who tended to play poker with their fates and dreamt of promiscuity. Moreover, a very small fraction of interviewed Baigas wanted to get back to Bewar — even if it was in their dreams. During a separate debriefing session with those who wanted to be polygamous in their dreams, the Baigas said that they did not mind day dreaming, and have fun at their own cost, once in a while! Nevertheless, the wish list brought out the Baigas' omnipresent but rarely articulated need for roads and tap water and not so much of a resounding need for irrigation, electricity and hospitals.

It seemed that with the banishment of Bewar, the free-spirit of jungle dwelling Baigas also died and they embarked on a pre-determined, regimented and predictable path to development and human well being!

This exercise reminded some of the septuagenarian Baigas of how Dr. Verrier Elwin had promised them that he would speak with Pandit Nehru, the then-emerging Prime Minister of Independent India, and convince him to help create some tribal reserve areas where relic tribes like Baigas could live freely. It seems Dr. Elwin was an advisor to Nehru but before he could actively take it up with him the former passed away in February, 1964 and Nehru also died three months later.

| Actual Demographic | Self Identification | Second Life Dream | Wish list for Baiga Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31-year-old, married male | Very rich with five wives | Very rich with five wives | Roads, tap water, hospitals |

| 48-year-old, married male | 48-year-old, married male | No changes | Jhum cultivation, tap water, electricity |

| 40-year-old, married male | 48-year-old, married male | No changes | Roads, electricity, tap water |

| 20-year-old, single male | 20-year-old, single male | No changes | Roads, tap water, irrigation |

| 25-year-old, married, pregnant female | 25-year-old, married, pregnant female | No changes | Better houses, roads, hospitals, irrigation |

| 38-year-old, married female | A man with five wives | A man with five wives | Roads, tap water, jhum cultivation |

| 42-year-old, married female, one child | A woman born in a city | A woman reborn in a city | Roads, hospitals, tap water |

| 18-year-old, male student | 18-year-old, male student | No changes | Roads, electricity, tap water |

| 45-year-old, widower | Very rich with five wives | Very rich with five wives | Roads, electricity, irrigation, jhum cultivation |

| 55-year-old, widow, two children | Very rich with three wives | No changes | Paved roads, electricity, tap water |

| 28-year-old, married male | 28-year-old, married male | No changes | Roads, tap water, hospitals |

| 26-year-old, married female, one child | 26-year-old, married female, one child | No changes | Roads, tap water, hospitals, irrigation |

Table 15. Dreams, Identity and Wish List of the Baigas.

It would have been a great day for Indian tribals if Dr. Elwin had successfully raised the concern of forest-dwelling aborigines of India with Nehru. The Hill Korwas, Birhors, Asurs, Chenchus, Kamars, Saharias and all Paharia tribes then might still be what they were and lived their dreams, instead of living a mainstreamed, co-opted and integrated nightmare in the Brahminical India, with no livelihoods and no lasting identity whatsoever.

All Baigas live in mud houses which they make themselves. They cover the roof with self-fired mud-tiles. An entire household of a Baiga whether within Baiga-Chak or not would have household goods worth Rs. 2,000 that include bedding, utensils and all the stored produce. However, there are some households that possess silver ornaments, owned by their women. Table 16 gives the status of silver ornaments owned by the women of the control Baiga group and from the BCB. Women of Baiga-Chak are much better placed than the Baiga women from outside in terms of ownership of silver ornaments, as each one of them has on average 192 gm. of silver compared to an average 60 gm. of silver owned by the Baiga women from outside of Baiga-Chak.

| Description | Metric |

|---|---|

| Number of Baiga Households with Women's Silver Ornaments | 161 |

| Weight of Owned Silver | 54.5 kg |

| Number of Control Households with Women's Silver Ornaments | 45 |

| Weight of Owned Silver | 2.7 kg |

Table 16. Silver Ornaments Owned by Baiga Households (N=300).

A similar comparison between the assets revealed that the BCB had 148 bicycles owned by 300 households and they also had six motorcycles. In comparison the control households of 45 Baigas had 19 bicycles and no motorcycle.

We conducted a series of three focus group discussions with a dozen experienced Baiga farmers in each location. The issue was their exploitation by non-tribals and high-handed behavior of the forest department officials towards them. We read out some cases which were about the exploitation of Baigas and Gonds, discovered and documented by W. V. Grigson (1940) as Enquiry Officer as he was particularly assigned the responsibility of finding out if there was any truth in large-scale exploitation of Baigas and Gonds by non-tribals in Mandla district by the Governor of Central Province and Berar, Nagpur. When listening to these cases, all participants were smiling and nodding and saying "yeah, yeah, it happens the same way to us these days also." Two of Grigson's cases are presented below.

"In a recent case No. 8 of 1939, not decided until February 5th, 1940, the Tehsildar of Dindori fined Lanitu Baiga of Bhariwal Rs. 10, plus Rs. 28 (as compensation, under section 26I) of the Forest Act, for the cutting of two sal trees. It is said that of the 4 prosecution witnesses, two Pardhans and a Gond had not seen the accused cutting the sal trees, and the whole case depended upon a retracted 'confession' made by his wife to the forest guard. The wife alleged in Court that she had been beaten by the forest guard to make this statement and that she had reported the beating to the police, who had sent her to the Assistant Medical Officer's (AMO's) office to be examined. For two days this AMO put off her examination and then went on leave for eight days. Finally, AMO examined her after ten days, on his return from leave and reported no visible signs of beating. The Tehsildar refused to pay any compensation to the Baiga woman because he found the forest guard innocent. But when this case came up in court the no protestations of forest guard's innocence or of Tehsildar made any impact on the judge and Tehsildar was asked to pay compensation of Rs. 1250, which was half year's income of forest department."

"Another case mentioned was that of the fining of six or seven Baigas in 1937 for killing a wild pig which they said had entered their fields. The case was reported by a notorious Hindu 'leader' who, according to the Baigas, only reported them because they refused to give him the meat. This man incidentally is the president of a village panchayat. This fine again was out of proportion to the financial status of the accused. Such a case may no longer be possible in view of the recent amendment of the Game Act permitting self-defense of crops (which also is unknown to the villagers), but there is no guarantee against misrepresentation of the facts or against the similarly heavy fine being imposed for a genuine case of illicit shooting without efficient supervision of the forest subordinates and lower Magistrates."

After listening to Grigson's cases each focus group related its own experience of exploitation at the hands of non-tribals and/or forest officials. We present in the box below one of these stories that showcases the events of exploitation of Baigas from Rajni Sarai village.

In the village of Rajani Sarai, belonging to block Samanapur, in Dindori district, 17 Baiga tribals used to cultivate 70 acres of Land. In its outskirts villagers were allowed to cultivate their land only if they paid the slush money at the rate of Rs. 500 per household to the forest officials. This process had started in 1975. In the year 2000, when, some of these villagers decided to discontinue paying this bribe, the senior forest department officials deployed their field workers for rounding up the ring leaders of this defiance. Consequently two Rajni Sarai Baiga residents, viz. Vikram Maravi and Lokram Dhurve, were booked and they were beaten up for seven days before being released. This move created panic among all Baigas and finally all of them ended up paying bribes to the forest officials again. Also the forest officials snatched the Baigas' implements like ploughs and seed drills of Rajni Sarai village. These incidents of intimidation and atrocities by the forest officials on Rajni Sarai Baigas did not end in 2000.

In 2005 these 17 families of the village sowed about 15 quintals of food grains in their 70 acres of land in the first week of June, which was supposed to produce about 300 quintals of food grains after the four months of crop-growing time. However, between the 5th and 9th of September, 2005, at the insistence of forest officials and the forest protection committee (a body of the local community members promoted by the forest department which is purported to protect the forest) of Rajni Sarai village, which had non-Baiga villages from Rajni Sarai panchayat, the entire standing crop of the Baigas (70 acres, almost ready to be harvested) was trampled down with tractors. Moreover, these Baiga households were debarred from getting wage labor related jobs from the forest department.

Finally, these 17 Baiga households from Rajni Sarai village were able to bag land rights for their 35 years of tilling in 2011, when they were issued land deeds for these erstwhile encroached lands under the Tribals' Forest Rights Act of 2007. They now hope against hope that perhaps they would not be victimized any more by the forest officials and their high-handedness will go away. All Baigas know that they could still be booked or falsely implicated by the forest officials for grazing cattle or for getting a head load of firewood, or even for collecting sal seeds, because a forest official still had all his magisterial powers intact.

The following folklore, presented in the box below was related to us by many Baiga headmen from the BCB as the proof of their right to claim benefits from the extant natural resources of the BCB.

Baigas are the sons of the Mahakaushal soil. They are the most ancient community of India that has been residing for tens of thousands of years. They call themselves "Kings of all Satpuda Hills and Vidhyas' jungles." The most coveted legend among Baigas, which they keep sharing with outsiders, quite often is about the origin of Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin and their worshiping soil-earth daily. This legend includes the Gonds as well because Gonds are said to be the second-born children of the Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin, whereas the Baigas emerged from the first-born children of the Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin. The legend goes as follows.

When God produced soil-earth, the next thing just after that he did was to create two humans. One of them was the nude male Baiga (Nanga Baiga) and the second one was the nude female Baiga (Nangi Baigin). Actually after producing soil-earth God had to fast for 12 days because owing to incessant rains he could not go out to collect food. When the skies cleared and the rains stopped God got up to go and find food but when he stood up he felt he was very dirty and started scratching his whole body. Layer upon layer of dust and grease-like debris started to fall from his scratching finger nails. God made two piles of the debris. He made a male Baiga from one pile and then made a female Baiga from the second pile. So God made Baiga and Baigin (female Baiga) out of his own body dirt. After creating the pair of Baigas God commanded them to leave earth and settle in God's middle kingdom. The middle kingdom had lots of water and many hills but soil-earth was nowhere to be found. God, after creating the Baiga duo, summoned four of his animal deities and sent them on a mission, along with the Baiga duo, to retrieve the soil-earth that was stolen by the snake-serpent of the nether world, the world that was located just below the middle kingdom.

These four animal deities arrived at the nether world and joined their forelimbs/hands together to pay obeisance to the soil-earth as soon as they met her. The four of them together, with great humility, requested her to accompany them to the middle kingdom where God had asked her to stay put with Baiga and Baigin. Soil-earth said that she would go away with them to the middle kingdom only if she knew the Baiga duo would respect her and worship her. She further told them not to worry, for the animal deities could not have vouched for the two Baigas. If the animal deities themselves worshipped her with full devotion and dedication she would be satisfied and would enter their bodies through their breath, and as soon as they left for the middle kingdom, she would go with them. The animal deities were concentrating hard with their eyes closed, their hands clasped and silently making salutations to the soil-earth. The act of worshipping was reaching its climax and soil-earth was almost inside the bodies of the animal deities when suddenly the serpent-king of the nether world rushed in dramatically and wrestled soil-earth with his full might and extracted the soil-earth from the teeth of the animal deities back into his clutches. The snake-serpent asked all four animal deities to go back to the middle kingdom bare handed.

The animal deities came back to the upper kingdom and met God. They told him what all had happened in the nether world. God asked all the animal deities one by one to come in front of him, open their mouths and show their teeth. God after examining their mouths told them the method to make a full-fledged soil-earth after collecting a few soil-earth particles from the gaps of their teeth that had gotten embedded when the snake-serpent was wrestling hard to retrieve her from their mouths. God asked the animal deities to rush back to the middle kingdom, prepare the soil-earth per his advice and help the Baiga duo to worship her, which would then happily embrace the whole of the middle kingdom. Without any further delay the animal deities flew to the middle kingdom. They acquired a huge cauldron. Each one of them extracted some soil-earth particles from his teeth then poured honey into it and finally poured some mahua liquor also, which consummated the formation of soil-earth making. All four animal deities kept stirring and churning the contents of the cauldron. After a lot of churning in the cauldron, soil-earth started boiling and falling out of the cauldron. The animal deities were desperate because they were afraid that if the Baiga duo did not come near the cauldron and worship the soil-earth, she may leave the middle kingdom and never come back there again. They kept calling Baiga and Baigin to come at once near the cauldron and worship soil-earth. But the Baiga duo was nude and they were ashamed to come out. The animal deities gave them loin cloth to hide their genitals and then the Baiga duo came near the cauldron and worshiped soil-earth with great gusto. They promised her that they would worship her daily and would never ever disrespect her. This is how soil-earth came to the middle kingdom and remained there.

Notes

[10] South Asia Pro-poor Livestock Policy Program, Good Practices Note, Making Modern Poultry market Work for the Poor — Learning from Kesla Project, Madhya Pradesh, PRADAN, 2009.

Photography and text © 2012, Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. All rights reserved.

Gangwar, M., and Bose, P. (2012), "A Sociological Study of the Livelihoods of the Baigas in Baiga-Chak Belt of Dindori, India." The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved

February 2, 2026,

from The Peoples of the World Foundation.

<https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/hosted/baigas/>