The Indigenous Tz'utujil People

Ethnonyms: Sutujil, Tzutuhil, Tz'utujiil, Tzutujil, Vinuk Countries inhabited: Guatemala Language family: Mayan Language branch: Quichean

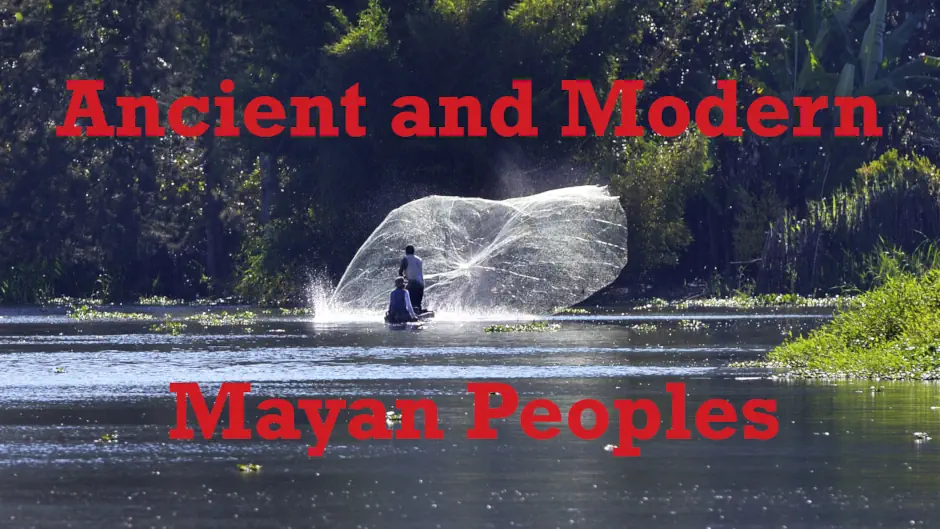

It's often said that all empires will eventually meet the same fate and die out. As sure as history repeats itself, we are seeing this today. But the reality is that as empires witness their own demise, while their power, wealth and influence wane and their population declines, their people seldom vanish. So it was with the Maya. During their Post-Classic period, beginning around 900 CE, they migrated away from the large centers that had sustained their empire and began anew. Out of this dispersion was established the Tz'utujil people. They became a recognizable ethnolinguistic group a few centuries later.

They were centered in what is now southern Guatemala, around Lake Atitlán. They continue to live in that area and, today, number around 80,000 — based on projections from the last census. Despite this number of speakers, Tz'utujil is considered an endangered language. There are many related factors contributing to this status. Although the Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages (ALMG) exists to promote the country's many indigenous languages, Tz'utujil speakers are discriminated against. Employment prospects are greatly enhanced by speaking Spanish. Younger people often speak the language to please — or simply to be able to communicate with their elders, but they more typically speak Spanish these days among themselves. Very few of its speakers can read or write the language.

Such loss of language among indigenous peoples does not only lead to loss of culture. It leads to the erosion of its speakers' world view as well as loss of indigenous knowledge. This was starkly demonstrated very recently. It's no coincidence that the Tz'utujil settled near a large body of fresh water with fertile land. The earliest settlers among them had just witnessed what drought can do. A sudden drought was one of the contributing factors in the decline of the Maya Empire. That knowledge helped them flourish for hundreds of years until the Spanish arrived. Using the familiar colonization tactic of divide-and-conquer, the Spanish enlisted the Tz'utujil's Kaqchikel Maya neighbors (and enemies — the Kaqchikel arrived in the area after the Tz'utujil) as war allies. Victory was swift for the Spanish. The Tz'utujil suffered massive loss of both land and population. Just as significantly, though, this loss also began the decline of their language. In October, 2005, the area was devastated by Hurricane Stan — much of the damage coming from mudslides. The small town of Panabaj lost around four hundred people; other small communities were wiped out. In San Lucas Tolimán, a few days later, government and NGO aid workers were distributing water rations for which the local Tz'utujil people had to queue.

It took a long time for the people and their communities to recover. The Guatemalan Civil War had ended only recently. At the time, the area was just beginning to develop as a tourism center. Most outside visitors did not leave the main town of Panajachel though. So the villagers had no choice except to revert to their traditional livelihood based on farming and small-scale animal husbandry. Historically the Tz'utujil have relied on the staple Mesoamerican crops and, for subsistence, they still do. Other crops are farmed these days including carrots, onions, cucumbers and tomatoes, and coffee, in particular, is a lucrative cash crop.

These days tourism is much more developed around Lake Atitlán. It contributes significantly to the local economy, but it comes at a cost. The black bass was introduced to the lake to make the area more attractive for recreational fishing. It became a predatory species causing problems for the local ecology and the traditional food supply. Pollution is now becoming a large problem also.

It's often reported that the Tz'utujil are among the most traditional of all surviving Maya peoples. The young girl pictured below supports that notion by wearing traditional Tz'utujil clothes. Actually, locals in traditional clothing — especially women and girls — is a common sight in Tz'utujil communities. A little scratching below the surface reveals much deeper tradition.

The history of the Spanish in the main Tz'utujil town of Santiago Atitlán is not the standard account of conquest. They arrived in the early-16th Century, but they had largely left a hundred years later. In addition, although they built a church there, they did not sack the near-by, ancient Maya center, Chiutinamit, which by then was, and still remains, a ceremonial site that actually predates the Tz'utujil. During the occupation, they seeded the town with houses of a brotherhood (in the Catholic sense of that term) to help them enforce religious conversion. The exact history from then until now is debated. However, it appears that many of these houses survived (whether in the exact same location or not) and over the years their Catholicism was syncretized with the Maya world view. Today, these houses are sites of Maya ritual and ceremony.

The best-known, and most accessible to outsiders, is the brotherhood of the Ri Laj Mam. They are the keepers of Maximón. Who is Maximón? Here again, the history is debated. Locals say he is the representation of ancient energy who is able to mediate between the living and the Creator. His manifestation in the material world is a one-meter tall effigy made from coral wood and dressed in sometimes traditional, sometimes modern clothing, including 36 neck ties. This effigy is moved to a different location within the town each year. People from both Santiago Atitlán and other lakeside Tz'utujil communities come to give offerings to Maximón and ask for his favors in return.

There are houses of other brotherhoods, mostly in Santiago Atitlán, where the Tz'utujil come to observe, participate in or lead ancient rites and ceremonies. In contrast, the photo above was taken inside the Catholic church in another lakeside Tz'utujil community, San Lucas Tolimán. Yet attendance at a nominally Christian (Catholic or Protestant) church does not define a person's religious belief or practice. A Tz'utujil may routinely go from their church to a brotherhood house or vice versa. Nor does spiritual life begin or end between brotherhood and church. While the brotherhood influence on religious life has dwindled (and, owing to a change in Guatemalan national law 75 years ago, has almost been eliminated from civil life), that of shamans has increased. As in most indigenous societies, shamans cross the boundary between spiritual medium and healer or practitioner of medicine. Thus a midwife might be considered a shaman, as might a herbal medicine specialist.

The word Tz'utujil means 'corn flower' in their own language. It should not be surprising that they chose this name. Corn (maize) has been sacred to the Maya throughout their history (one of their gods is the God of Corn). It is believed that this may be due to the same nine-month growth cycle as human gestation. So, in the photo above, Tz'utujil women in an open air marketplace may not be handling corn to decide whether to buy it. They may instead be performing a religious ceremony. Even though their ancient ancestors had writing, much of their traditional history has long been oral. This has allowed the preservation and survival of the "old ways" despite colonial attempts to eliminate them from the very beginning. Such tradition takes many forms including, for example, poetry, music, song, ritual and textile weaving. Close study of these has revealed much of their indigenous knowledge — although much remains uncovered.

Along with their Kaqchikel neighbors, the Tz'utujil face many challenges in the modern world. While they have certain rights under Guatemalan law, like most indigenous people the world over, many of those rights are, in practice, denied them. This is especially true in areas such as public health, education, employment/economic opportunities and political participation/representation. This in turn leads to their overrepresentation in terms of poverty. Due to both tourism and the desirability of Lake Atitlán for permanent residence, the local economy has been booming for those Tz'utujil who are able to establish businesses that cater to the hospitality sector. (Of course, this has been impacted recently by Covid-19.) Yet the lake is beginning to suffer ecologically from a lack of planning and management. According to the organization, Viva Lago Atitlán, unless action is taken soon, the lake may deteriorate irreversibly in the next few years. That would be the greatest setback imaginable to the indigenous Tz'utujil people.

Photography copyright © 1999 -

2026,

Ray Waddington. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 1999 -

2026,

The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R. (2020), The Indigenous Tz'utujil People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Tz'utujil>

Web Links

Maya Timelapse (short film on YouTube)

A Deeper Look Into the History of Ancient Maya Tradition in Santiago, Lake Atitlán

The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan: The 'Flowering Earth Mountain'

Books

Carlsen, R.S., (1997) The War for the Heart and Soul of a Highland Maya Town. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Freidel, D., Schele, L. and Parker, J., (1993) Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.