The Indigenous Tzotzil People

Ethnonyms: Batsil K'op, Tsotsil, Tzotsil Countries inhabited: Mexico Language family: Mayan Language branch: Tzeltalan

Over a quarter of a million Tzotzil live in the highlands of central Chiapas State, Mexico. They are the neighbors of their

linguistic cousins, the

Tzeltal. While their daily life has changed

dramatically in the two thousand years since their ancestors came here, it is also in many ways remarkably similar. In their

language "tzotz" means wool. Indeed wool is a primary material from which they make clothes. But in the ancient Mayan

language "tzotzil" connotes "bat people." It is this latter interpretation that Spanish invaders used to distinguish the

Tzotzil from other linguistic groups when they first arrived here. An early Spanish historian even reports their worship of a

stone bat as one of their poly-gods.

Over a quarter of a million Tzotzil live in the highlands of central Chiapas State, Mexico. They are the neighbors of their

linguistic cousins, the

Tzeltal. While their daily life has changed

dramatically in the two thousand years since their ancestors came here, it is also in many ways remarkably similar. In their

language "tzotz" means wool. Indeed wool is a primary material from which they make clothes. But in the ancient Mayan

language "tzotzil" connotes "bat people." It is this latter interpretation that Spanish invaders used to distinguish the

Tzotzil from other linguistic groups when they first arrived here. An early Spanish historian even reports their worship of a

stone bat as one of their poly-gods.

Today some Tzotzil call themselves "Sotz'leb" which means

"bat people" in their dialect of the language.

Today some Tzotzil call themselves "Sotz'leb" which means

"bat people" in their dialect of the language.

Probably the largest change in the entire history of the Tzotzil is happening today as they are abandoning their traditional

lands. To some extent this is the same global trend that we see among rural peoples everywhere, and it is driven by economic necessity.

But, in the case of the Tzotzil, this response is not always voluntary. Indigenous groups in this area of Mexico

are having their lands taken away from them, by force, and with the consent and active participation of the Mexican government.

It is ironic that this abandonment is their reaction to present-day occupation and possession

of the very land that was first stolen

from them, then "granted" to them and then later again stolen from them by Spanish invaders.

It is ironic that this abandonment is their reaction to present-day occupation and possession

of the very land that was first stolen

from them, then "granted" to them and then later again stolen from them by Spanish invaders.

Yet some Tzotzil have reacted differently than their peers. The Tzotzil are among the most ardent supporters of the

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista National Liberation Army). The EZLN are commonly known as the

Zapatistas. They are so named in recognition of the zapatismo social and political cause popularized by Mexican revolutionary leader

Emiliano Zapata (1879 - 1919).

A hundred years ago he too created an army of indigenous people fighting for their land rights.

A hundred years ago he too created an army of indigenous people fighting for their land rights.

It is no coincidence that the EZLN came to prominence — and world attention — on January 1, 1994. That is also the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) became effective. The EZLN feared (and recent history is validating their fear) that NAFTA would have great negative impact on Mexico's indigenous people.

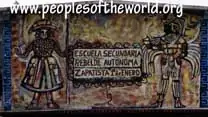

To some extent the Zapatistas have succeeded in their aim to gain autonomous self-rule — albeit unilaterally declared. Part of that

self-rule is evident in the education of their children. The Zapatista Autonomous Rebellious Education System (SERAZ) is an

alternative to the Mexican national education system.

"Teachers" in schools run by SERAZ are volunteers and are more like facilitators

of education than standard teachers.

The curriculum is very similar to the national one except students are taught their indigenous language

as well as aspects of their cultural history.

To some extent the Zapatistas have succeeded in their aim to gain autonomous self-rule — albeit unilaterally declared. Part of that

self-rule is evident in the education of their children. The Zapatista Autonomous Rebellious Education System (SERAZ) is an

alternative to the Mexican national education system.

"Teachers" in schools run by SERAZ are volunteers and are more like facilitators

of education than standard teachers.

The curriculum is very similar to the national one except students are taught their indigenous language

as well as aspects of their cultural history.

Tzotzil students should have no difficulty relating to these cultural history lessons. They are surrounded by their living culture

in their daily lives. When I visited a Tzotzil SERAZ school the students interrupted their lesson and insisted on

giving a demonstration of traditional Tzotzil dancing that is part of youth courtship.

Tzotzil students should have no difficulty relating to these cultural history lessons. They are surrounded by their living culture

in their daily lives. When I visited a Tzotzil SERAZ school the students interrupted their lesson and insisted on

giving a demonstration of traditional Tzotzil dancing that is part of youth courtship.

In another Tzotzil village a woman cooked tortillas, from freshly ground maize, over an open fire. Her preparation and cooking techniques

were no different from those of the ancient Maya. In the same village another woman demonstrated traditional weaving on a back-strap loom.

Like some other mothers in this and other Tzotzil villages, she has taught her female children

to weave cloth and make clothes from it. Her raw materials come from the same sources her ancestors used.

Like some other mothers in this and other Tzotzil villages, she has taught her female children

to weave cloth and make clothes from it. Her raw materials come from the same sources her ancestors used.

Early Maya culture revolved around a complex world of science and religious beliefs.

While their understanding of science — particularly

astronomy — has only recently been recognized, their religion was confronted immediately by the Spanish. The result was the early assimilation

of Catholicism into Maya religious practice. Today most Tzotzil follow a fusion of their religious heritage and Catholicism.

Recently, some Tzotzil communities have replaced Catholic influences with Protestant ones. Some have converted to Islam.

Recently, some Tzotzil communities have replaced Catholic influences with Protestant ones. Some have converted to Islam.

Many Tzotzil still maintain the religious practices of their ancestors.

The lady pictured above right is the wife of an elected religious caretaker. She is blessing the Maya cross outside their house.

She will do this at key times in the day, every day, for the year that her husband serves in his role. Caves and mountains are still among the sites

where the Tzotzil perform ancient rituals.

As we approached one such holy site we found women washing clothes in a stream. At the

beginning of each 20-day cycle of the Maya calendar

the clothes of the twenty saints are ceremonially brought to this same holy site,

washed, dried in the sun and ceremonially taken back to the church where the saints are dressed again.

As we approached one such holy site we found women washing clothes in a stream. At the

beginning of each 20-day cycle of the Maya calendar

the clothes of the twenty saints are ceremonially brought to this same holy site,

washed, dried in the sun and ceremonially taken back to the church where the saints are dressed again.

Observation of such religious tradition involves not only the living. The dead also play a role in Tzotzil spiritual belief. Death is accompanied by burial which includes artifacts for the deceased to take to the next world. The deceased's soul is kept safe in the next world by ancestors until it is time for reincarnation. In a cemetery the color of the Maya cross on the grave tells the approximate age at which the person died. White crosses are on the graves of children while black indicates a middle-age death. Only the few grey crosses represent those who lived to full life expectancy.

Photography copyright © 1999 - 2026, Ray Waddington. All rights reserved. Text copyright © 1999 - 2026, The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R., (2008) The Indigenous Tzotzil People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Tzotzil>

Web Links Schools for Chiapas Introduction to the Tzotzil Language Tzotzil Communities of the Highland of Chiapas Los Tzotzil (en español) Die Tzotzil (auf Deutsch) Tzotzil-ii (in romana) Books Gossen, G. H., (1999) Telling Maya Tales: Tzotzil Identities in Modern Mexico. New York: Routledge. Gossen, G. H. (Ed.), (1993) South and Meso-American Native Spirituality: From the Cult of the Feathered Serpent to the Theology of Liberation. New York: Crossroad. Collier, G., (1975) Fields of the Tzotzil. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.